Entering Adulthood

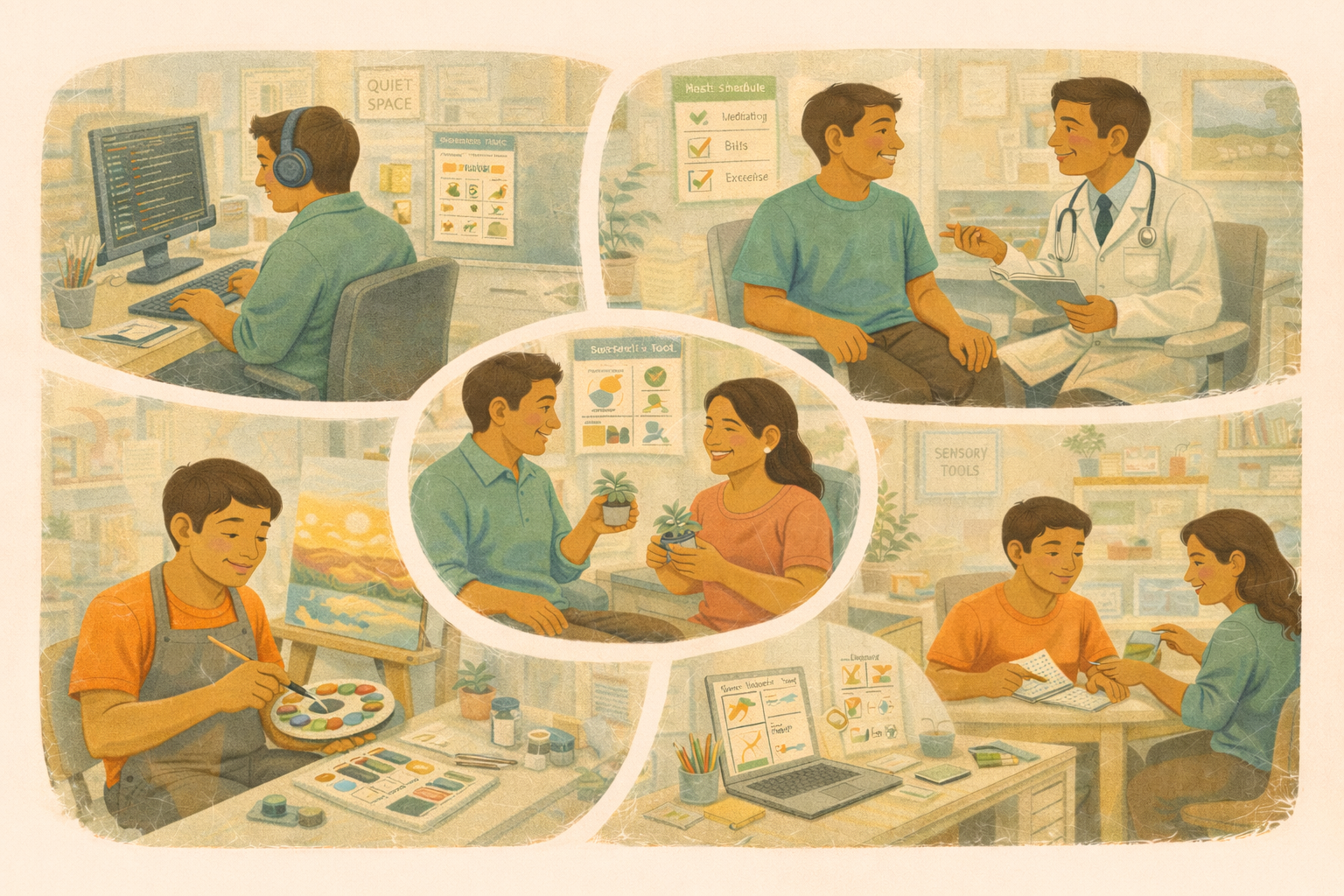

Entering adulthood marks a major life shift. For young people on the autism spectrum, this milestone often comes with exciting new possibilities alongside sudden changes in supports, routines, and expectations. If the teenage years were shaped by school-based services, structured schedules, and guided planning from teachers and family/ caregivers, adulthood can feel like stepping into new and unfamiliar territory. As independence grows, so does the need to reimagine support. The goal is not to remove structure but to help the young adult co-create new ones suited to their strengths, interests, and evolving identity.

The “Services Cliff”

In most education systems, the rights to school-based support and services—like individualized education plans (IEPs), transportation, occupational and speech therapy, or transition counselling—end around age 18 to 21. For many autistic young people, this shift brings what researchers call the “services cliff.”

The “cliff” refers to the steep drop-off in structured supports that happens after school ends. In one study, while 87% of students on the spectrum received services during school, only 26% continued to receive them afterwards. This leaves many families navigating complex adult systems, new eligibility criteria, and bureaucratic layers just as the young person is trying to build independence.

Without preparation, this transition can feel like moving from a well-marked path to an unknown stretch of road. The impact can include delays in vocational growth, challenges in self-management, and emotional strain. Yet this transition point is also a chance to reimagine support—from formal, school-based systems to community-linked, interest-driven opportunities.

Transition planning: beginning in the teen years

Early planning is the strongest protection against the services cliff. Ideally, this begins by age 14–15, when school, families, professionals associated and the young person can start visualizing adult life. Transition planning is most successful when it centers the young adult’s voice—what they enjoy, what they want to explore, and what kind of life balance feels right. When we speak of independence, especially in the context of young autistic people moving into adulthood, the image is often one of “doing everything on my own.” But for many autistic adults, independence is more nuanced. Research shows that autistic adults define and experience independence in ways that differ from the traditional, neurotypical narrative — and that accepting support is often a key part of that independence. A ground-breaking qualitative study of autistic adults in the UK found three core themes:

-

“Independence is ‘not a one-size-fits-all’” — Autistic adults emphasised that independence is a relative concept, unique to each person’s preferences, strengths, supports and life context.

-

“There is no one definition or concept of independence for autistic people; these are relative and uniquely individual.”

-

“Being autistic has its setbacks in a neurotypical world” — Many autistic adults face structural, sensory, communicative, and mental-health barriers when trying to live independently in what is still often a neurotypical environment.

-

“Finding ways of making it work” — Autistic adults highlight strategies: seeking help when needed, building scaffolding, choosing supports, recognising fluctuations in capacity, and redefining independence as making choices rather than doing everything solo.

Key elements of transition planning include:

-

Accepting help is not a failure of independence; it can be integral to it.

-

Exploring strengths and interests: Identify what the young person enjoys—creative arts, technology, helping others, research, nature etc.—and link these interests to future work or learning options. For the teenager to choose interests, they must have been exposed to various opportunities, responsibilities, and support as they grow up, giving them the fair opportunity to choose their strengths, challenges and interests.

-

Building life skills: Daily activities like food preparation, budgeting, travel, and communication all contribute to autonomy. Encouraging routine practice of these, builds confidence.

-

Gradual independence: Shifting small responsibilities—scheduling appointments, managing an allowance—fosters self-trust and reduces future overwhelm. Mapping adult supports: Learn about local vocational, therapy, and social programs early to avoid gaps after school.

-

Emotional preparation: Talk about change, uncertainty, and growth. Reinforce that every adult continues learning adaptive skills throughout life. Independence often relates not just to functional skills (cooking, laundry, travel) but to emotional, cognitive, social dimensions: self-advocacy, recognising when one needs rest, balancing strengths and limits.

-

Planning is not a one-time event but a continuous dialogue that evolves with the person. In sum: a transition plan that frames independence as “having choices, making decisions, finding the support you need and growing your capacity to act” is more aligned with autistic adult experience than “doing everything by yourself from day one.”

Emotional impact of sudden change in structure

For many autistic adults, the end of school brings both freedom and uncertainty. The removal of routine—fixed schedules, daily travel, known teachers—can trigger feelings of anxiety, loss, or aimlessness. Families may observe changes such as increased stress, withdrawal, or frustration. These are often responses to loss of predictability, not a lack of motivation.

Parents and carers too experience their own transition: from being organizers of services to partners in adult life. Recognising that this shift can feel disorienting is essential for both sides. Building emotional resilience means allowing space for grief over what’s ending—and curiosity for what’s next.

Ways to ease this emotional adjustment include:

-

Creating new daily or weekly structures that include meaningful activity and downtime.

-

Connecting with peer groups or mentors—especially autistic adults who’ve navigated similar transitions.

-

Seeking counselling or peer support for managing anxiety, uncertainty, or family stress.

-

Celebrating small steps toward independence, rather than expecting instant readiness.

In the Indian context

In India, adult services for autism are still emerging. Many families rely heavily on school systems, and when these end, there can be very few adult-focused programs or agencies. Public awareness is improving, but gaps remain in supported employment, post-school education pathways, and community-based living options.

However, India’s strong family and community networks can also be sources of resilience. Families can build local support through self-help groups, NGOs, and peer networks. Encouraging inclusive college programs, vocational training, and flexible workplaces contributes toward a more welcoming adult landscape. Planning early, staying connected, and using collective advocacy are key tools.

Moving forward with hope

Adulthood is not a single leap—it’s a series of steps, sometimes uncertain, often full of possibility. The “services cliff” is real, but it doesn’t have to be a fall. With preparation, collaboration, and community, every young person can enter adulthood with purpose and dignity, supported by the scaffolding that lets them thrive on their own terms.